A Life

Some books stare deep within, and offer you a perspective that – prior to – you didn’t think would ever be recorded. Sure, we know deep down that our experiences are not all that unique – that surely someone has lived similarly, made equally stupid decisions, and had a number of veritable successes to which we can relate. But it’s so UNLIKELY that they would write these down, or that we would find the records. And yet, here we are.

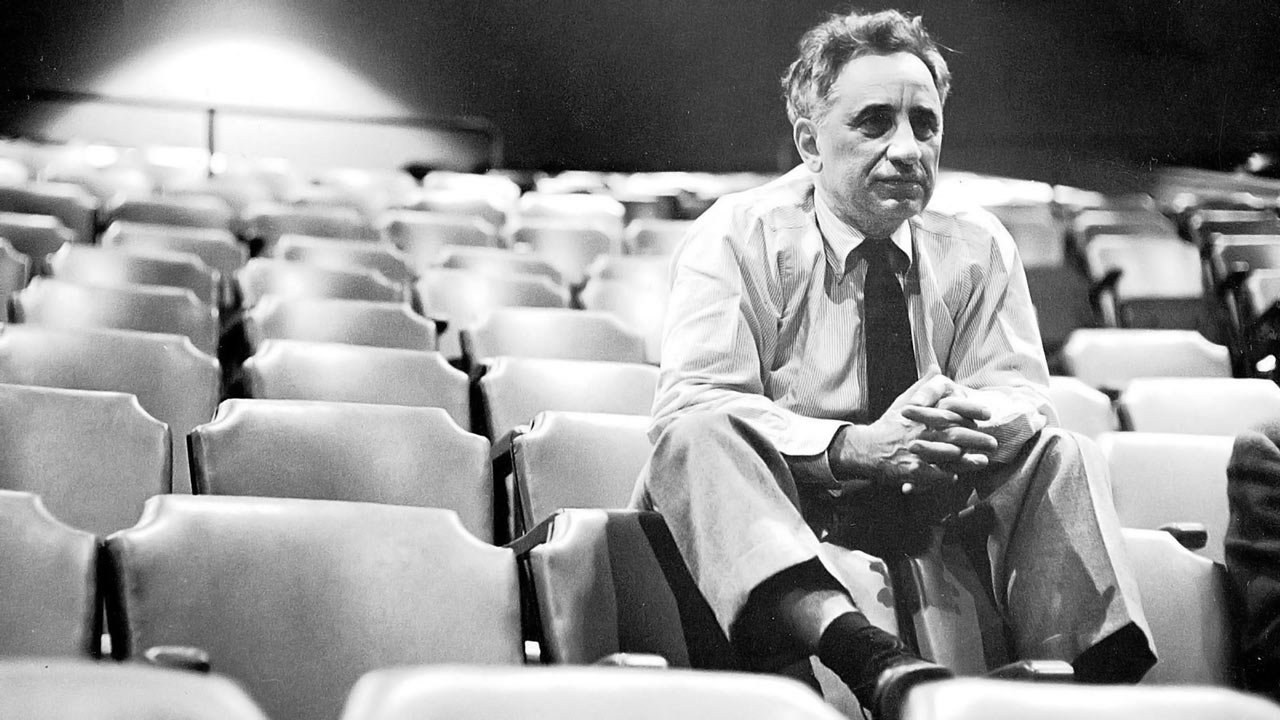

Elia Kazan is one of the greatest American film directors who ever lived. He discovered the talents of Tennessee Williams and made him a star playwright, he worked with Marlon Brando and brought his name to platinum status, and he built prolific careers for actors like Andy Griffith, Robert De Niro, Warren Beatty, Karl Malden, Patricia Neal, Julie Harris, and – albeit cut short by circumstance – James Dean. He worked side-by-side with prominent authors like Art Miller and Clifford Odets and John Steinbeck. And he contributed some of the greatest performances to America’s filmography. His life, however, was a goddamned mess.

I’ve read far fewer biographies than other works, but only a handful really standout. Thomas Hauser’s biography of Muhammed Ali was one of the more compelling, but it was not authored by the subject of interest. Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations was a lucid compilation of his life lessons, but far less confessional material than Kazan’s tome. (At nearly 850 pages, it takes some diligent commitment.)

Despite being a talented writer, the book was painful. I don’t mean that it’s hard to read or boring; it brings up so much shit so fast that it can be difficult to adjust. I don’t know anyone who is that open about the minute, embarrassing details of his or her life – it’s doubtful we could even maintain a friendship. It’s the kind of material where you latch on to understand its application to your own life choices; but also push away the details that don’t relate to you, yet you empathise with the person suffering. One benefit is that there is adequate balance between the aspects Kazan wants to divulge as a way to process his personal trauma, and his thorough explanation of an artistic process that made him one of the absolute best film directors of all time.

One thing that stood out to me was how, when he’d get super close to the root cause of his life’s problems, he would ultimately divert the topic and bail. I think this is why screenwriters talk about never picking your own life as a subject: to effectively write, you need to fully understand the problem and its solution, and you can only get so close to solving a problem that still lingers. This should not spoil the book in any way, as he does make some profound realisations. It’s just a grueling observation of life in ways that make you confront your own inequities.

In conclusion, I’d like to include an excerpt near the end of the book. It’s a radically different tone from the rest of his writings, but I think the message was the closest he got to realising his own dramatic arc. I know it’s lengthy, but I feel it’s well worth it:

“…[Clifford Odets] glowered at his nurse, a fine, patient woman, and declared, ‘I want to shout, I want to sing, I want to yell!’ The nurse, who’d heard it all before, said, ‘Go on, shout, yell, sing if you want to!’ Then he tried, I remember he did try. But his shouting days were over. He was a might sick rooster. So he lay there and glowered angrily at the world in general and whatever it was that was cornering him now. No longer able to avoid the tragedy he’d lived or the tragedy that he was or the thought of what he might have been, he beckoned to me to lean closer, and he whispered – I remember the words well – ‘Gadg! [Kazan’s nickname] Imagine! Clifford Odets dying!’

“What I’m saying to you through this true story is that the chance we have here won’t happen again. The series of accidents and aspirations, along with real estate deals, civic concern, and guilt feelings, and the desire of the rich men to have their names remembered after they die, all those piled together produced this surprising opportunity for us. It won’t happen again. Not for many years! So let’s not lose it.

“The tragedy of the American theatre and of our lives is what could have been. Forces dispersed instead of gathered. Talents unused or used at a fraction of their worth. Potential unrealized. We all know our problems. We are not kids, we are not students. We know we are here on short leases. It is now time to stand up for ourselves before we disappear from the scene.

“The man who, in the forties, promised to be the Hamlet of our time has yet to play Hamlet, or anything like. The man who could have been the Lear of this generation is playing a sheriff on a TV series. I don’t think he plays sheriffs very well. He could have been a great Lear. The man who could have been the greatest actor in the history of American theatre is sulking on a grubby hilltop over Beverly Hills or on a beach on the island of Tahiti. What happened to them? They don’t know. Don’t look down on them. They are not weaklings. They were idealists too. Nor are they corrupt, confused, or sicker than most. They are your brothers.

“What is so terrible in our society is that people like ourselves are only rarely in control of their own lives and destinies. We don’t do what we want to do. We do what we think we have to do. Or what’s worse, what other people want us to do, what ‘they’ – whoever ‘they’ are – want us to do. We settle for co-starring roles on a TV series we despise, for the approval of our agents and a better contract this year than last. When we go from flop to flop we are terrified. When we find ourselves in a hit, we are bored to death.

“Now we are going to try to do something we respect for a change. It is hazardous. When you say something is difficult, you are saying it might not work. We are here to attempt a birth. All births are difficult. Look at a baby’s head. Don’t you wonder how it managed to get through? Like everything else worth doing, it is impossible.”