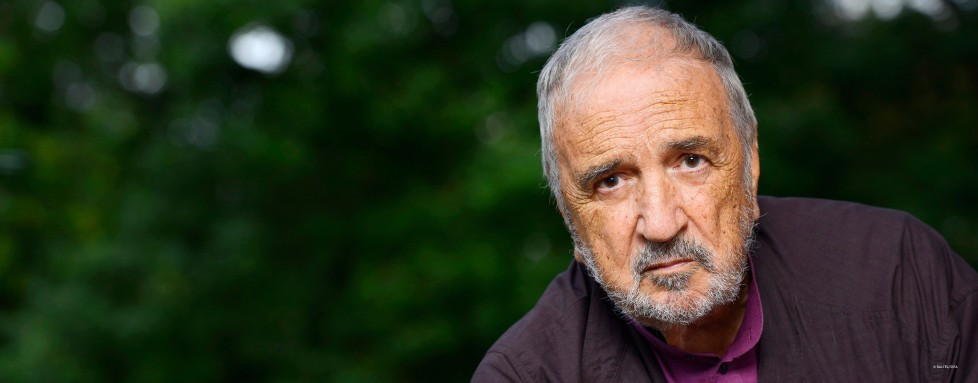

Beautifully crafted essays by French film theorist Jean-Claude Carrière, who was himself a highly prolific and successful screenwriter – working for the likes of Buñuel and Volker Schlöndorff. And the man has a certain command of language that is equal parts moving, inspiring, clear, and devastating. This book not only covers the vast distance of the evolution of visual linguistics behind the ever-evolving cinematic language, but it reinvigourates your imaginative “muscles.” He calls out your shit – the stuff that ruins your creativity – and he gets you to work through it.

Movies have forever changed the human landscape, both internal and external – especially when considering how we view each other and how we view ourselves, compared to…say…the old Master Thinkers and Philosophers of ancient Greece, for example. And yet, with all this technological development and our constant, ever-increasing exposure to new media, the question still remains: is cinema young or old? There is no clear answer.

Carrière masterfully interweaves timeless observations with research that was contemporary in the 90s, and bundles the proof neatly with intriguing, insightful stories that delight you as you read. Even if you’re not a film buff, there’s much to appreciate about this title – especially the way he writes and his humour.

One particularly moving passage recounted how, after being imprisoned a decade without access to media, ex-convicts would be completely confused by modern films and could not follow the sequence of events within the plot. Just like language, film techniques and meanings evolve, are filled with mistakes and misunderstandings, become trite and vapid, and circle back to new meaning. As the Indian proverb says, “God is only interested in beginnings….”

I wanted to cite the following passage, which pertains to the manipulation of news stories for dramatic effect, because it holds prevalent meaning for me:

“Sometimes it is enough to be forewarned, to have a lucid grasp of the language of film, for every TV news program to become an interesting decoding exercise. We can then look with new eyes at the images that bombard us (nobody ever wholly escapes them), anticipating blind alleys, technical tricks, omissions. Our habitual passivity can give way to wakefulness, to curiosity, to a critical eye. A necessary, salutary attitude and – doubtless for that very reason – a perpetually threatened one. But how many people will take the trouble, or are informed enough, to open their eyes, to see differently? Most of the time we stare supine and dull-witted at the image we are shown and the sound we are made to hear: dull and unreacting. Sometimes we hear that these are ‘exclusive’ pictures – meaning that they have been acquired as a result of sub rosa deals and fees higher than the competition could afford. We are being tempted with promises of horror. After one railroad disaster I even heard a reporter say, ‘With luck, we will be able to show you the footage of this horrible accident later on in the program.’ Every professional announcer is to some degree an actor.”

There is so much covered in this tiny book that I can’t really do justice to any review of it. He talks about damn-near everything: relationship in art, the tricks the mind plays on itself, the frustration of trying to find creative balance between exploration and reflexion, and the list goes on. And they aren’t necessarily neatly compiled (in the most positive way, it ties all the elements together, even though it may be at the cost of convenience). I would recommend taking notes; but don’t be off-put: this is a remarkable read.

I had written a longer review, but had ended up quoting so many passages that it was like I was rewriting his book. I think that exercise could be useful, if for no other reason than to sort the immense volume of data packed into those narrow bindings. I didn’t even choose the best quotes! But I do find value in some particular phrases, such as this one – that could really use some context that is not here: “The filmmaker is the heir of the great storytellers of the past, and the keeper of their tradition.”

When Carrière met up with Oliver Sacks, he asked him “What is a normal man?” After some time, Sacks replied that he thought a normal man was one with whom understood his own story (to its full capacity). I think the deeper joke – or the sad tragedy – is that who we are is defined by our stories. Without them, we are aimless – evanescent ghosts without substance that whisper our sad ideologies to those that, even if they could hear, wouldn’t care. Knowing where we come from and where we are going is a profound aspect of our character, and it was refreshing to read from someone who not only understood these nuanced aspects to media – but also someone who cared so deeply about movies that it ends up reminding you of your own occupational divinity…your reason for pursuing this craft. We should all try to find teachers that can help transform our lives. I’ve been fortunate to experience so many of them remotely or from beyond the grave, but nothing beats the real thing of a teacher beating sense into you.. If your heroes still happen to be alive, you should set down to write them a letter immediately. You’ll only regret it if you don’t follow through….